The Truth Incarcerated

Translated by Raquel Martinez

To the young women imprisoned for

participating in the protests.

¿How will the rain be heard in the cells of El Chipote?

(once upon a time that was the name of the encampment of Sandino) (I) imagine the sound on the roof and through the windows, young women grateful for the cool air seated on the ground with their backs against the wall remembering the noise of the patios of their homes the voices of their mothers or their bustling steps heading to remove clothes from the clotheslines young women, forced to prison beds, to putrid smell and costrictment Amaya, Victoria, Elsa, Yaritza with their faces free from marks or wrinkles still preserving the sound of laughter in the marches the exhaustion of protest, the enthusiasm of thought who waged battles so that they would not die again the dead, the comrades and their names those who were written on cardboard posters

walking through the multitude.

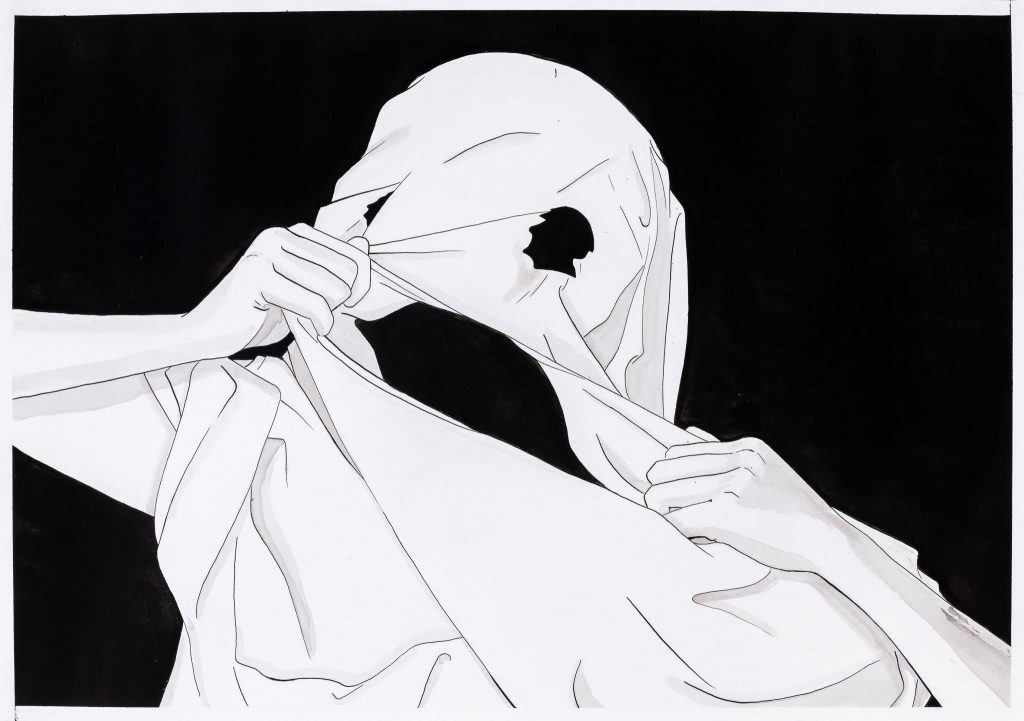

They didn’t imagine then that in that country where they grew up they would be ripped out of their homes they would be enveloped in blue cloth the sun would be taken from them.

They had not been born into a country where those things kept happening. Where the histories told as little girls would be repeated histories of massacres and prisons and torture.

They didn't think it could happen to them diligent students earnest students in the final years of their studies.

But there they are listening to the rain and the list of accusations mount against them. The weapons on the ground as they were shown to the press, stating the young women were carrying them weapons they had never seen before.

The incarcerators spare no attention to their explanations, but they recite them in the dark of the cells. The arguments of their innocence fall like the rain on their patios water that is lost in the acequias water that no power collects nor wants to hear.

Nothing they say will be used in their favor, because the truth, too, spends its hours with them in the dark cells where it rains.

[avatar user="martinez" size="thumbnail" align="left"]Raquel Martinez[/avatar]

[bg_collapse view="link" color="#4a4949" icon="arrow" expand_text="Translator’s Note (English)" collapse_text="Hide" ]

Between the Lines of “The Truth Incarcerated”

When I first met Gioconda Belli as a little girl, I was enchanted by her curly hair and her bright eyes. I told her, with a certainty I now envy, that I wanted to be an author like her when I grew up. Though I can remember her smiling at me, giving me encouraging words, I now know that following in Gioconda's footsteps is more than a process of writing. Gioconda Belli is a Nicaraguan woman who not only occupies the role of renowned writer but also is a fierce human rights activist and protester. Forty years ago during the first revolution, she served as a behindthe-scenes spy for the revolutionaries. Now, at the renewal of rebellion, she is on the front lines with her pen as a sword.

Barely had the ink dried on new history textbooks when Nicaragua began a repetition of violent events from about forty years ago. It is a battle against dictatorship that, arguably, never ended in the first place. A rebellion where the soldiers are masked university students fighting for a better future against a government that cares for nothing but their submission. Driven by the determination to spotlight the traumas that the Nicaraguan people are currently undergoing, I emailed Gioconda Belli for the first time in years, in search of a powerful message to translate to a wider audience. She responded on the same day, sending me her most recent poetic work, titled: "La Verdad Encarcelada."

In the past, my experience with translation had revolved primarily around the translation between English and Spanish of my own creative works. As only the writer fully understands the intention behind a piece of writing, converting my own text to another language was a natural process that came with little struggle. I also had, occasionally, dabbled in translating long passages between English and Spanish for my family's business website. This form required little

more than direct literal translation and, because it too came with such ease, I had admittedly not spared much thought for the nuances and meanings behind the words. I completed these translations in one sitting, mostly without referencing a dictionary or thesaurus. Such is being born into two languages, that one rarely notices the intricacies of either due to the comfort of both.

However, from the moment I set out to translate “La Verdad Encarcelada,” it demanded another process entirely. I could no longer neglect to notice the discrepancies of Spanish and English as they were brought starkly to the forefront by the refinement of poetic language. Poetry, described as "language of the soul" by translator Mireille Gansel, was less of a literal conversion between two languages and more a translation of a single soul into a new body (6). I found myself inspired by Gansel and her experiences in her memoir Translation as

Transhumance with translating languages marked by historical and ongoing traumas. Overwhelmed at first and attempting to confront my insecurities about translating such a long work, consisting of 44 lines, I decided to simply translate the poem literally before delving deep into its nuances. Only after that did I write out each line, both original and translated, on individual pages of my little notebook. Influenced by Gansel’s translation process, I scrawled a spiderweb of thought over the pages as I scrutinized each individual word’s meaning as well as its contribution to the entire poem.

From the onset of translating "La Verdad Encarcelada,” or "The Truth Incarcerated," I encountered syntactic and semantic difficulties. The first of these difficulties presented itself promptly to me in the 3rd line of the poem with the word "imagino." In English, this single word is literally translated to "I imagine." Before, I had never profoundly reflected on the placement of

self or subject in single words in Spanish, yet now it posed a provoking complication. Adding "I" into the translation would be a proclamation of a direct point of view that was absent in the original, but avoiding the addition meant either changing the tense or the context of the word itself. Using something like "imagine" would sound like a prompt to the reader rather than the initiation of a string of descriptive language. Meanwhile, "imagining" would leave the reader distracted and wondering who could be doing the imagining. Though I remained unsatisfied, I found myself settling on the awkward yet ambiguous "(I) imagine.” This complication of subject defining words continued on throughout the poem, appearing frequently through, “las,” “les,” and “los,” which I often had no choice but to translate into the vague words of “they” or “them.”

Gioconda also makes use of poetic license, which made finding an adequate English translation all the more difficult. “Apretujamiento” in line 10 is not even a 'real' word in Spanish. It combines apretar "to squeeze" with the ending miento, equivalent to the English "ment," creating a word similar to "squeezement." I found dissatisfaction in translating this morphed word into "confinement" or "constriction" as it never fully captured the feeling of immediate action contained in a word like "apretujamiento." In the end, I found myself staring down at my own self-made word: “costrictment." Too me, it came as close to the meaning and Frankensteinlike feeling behind "apretujamiento" that I could find.

However, what perhaps what gave me the most difficulty was the succession of powerful and action-packed verbs in lines 20 to 23.

"arrancarían"

"enfundarían"

"arrebatarían"

Possibly originating from my childhood surrounded by farm life, the word "arrancar," meaning to pull or tug, maintained the connotation of the ripping up of rooted plants after harvest. For this reason, I settled on "ripped" to convey the violence of the Spanish word. “Enfundarían" in the 22nd line, has a myriad of meanings depending on the context, such as to cover, to enclose, or to sheath. However, in an attempt to maintain the feeling I interpreted from the poem, I settled on the word "enveloped." However, for the nuanced "les arrebatarían el sol," I was forced to rearrange the sentence to retain the original meaning. Here, the subject is changed from "las," referring to the young incarcerated women, to "les," referring to the unnamed others who were performing the “ripping” and “enveloping” actions in the previous lines. With no way of defining this difference in English, the line became: "The sun would be taken from them." Though I had initially intended to translate "arrebatarían" as "seize," the Spanish word can also be used to express the act of taking someone's life. In this way, Gioconda subtly indicates the death of the sun, something that I attempted to retain by translating the word as "taken."

The poem also gave me pause when deciding what distinctly Spanish aspects I would leave in and which I would remove. In translating, it was a deliberate decision to leave in the inverted question mark, so distinctive to the Spanish language. Now, in the age of technological communication and growing English dominance, the inverted question mark is rapidly disappearing from existence. Due to this, I felt that it would be almost sacrilegious to remove and instead left it as a ghost of the Spanish language tradition on the English version. I encountered another instance of Spanish history in the word “acequias” near the end of the poem in line 39. Acequias can mean drought in Nicaraguan Spanish, but also is the name of Spanish colonial watercourses used for irrigation as far back as the Roman times. Translating this ambiguous

word to English would mean making a choice for the reader between these two definitions, a choice that I instead neglected to make by leaving it in its original form.

In translating “The Truth Incarcerated,” I had to constantly keep in mind both the historical contexts of the language, as well as the shifting meaning of words in the face of the

Nicaraguan revolution. I was reminded of the way the German word “sensibel” had changed for Mireille Gansel from “fragile” to “sensitive” after taking into account the traumas the language had undergone (34). To reflect the language and feeling of Nicaraguan rebellion, I made subtle changes such as translating “sin” in line 12 as “free from” rather than “without.” However, I found that the Spanish language itself holds poetics that no words in the English language can reflect. A subtle rhythm like the rainfall was lost.

Upon encountering this dissatisfaction, I asked Gioconda what she was originally feeling when writing the poem. She told me how she had been thinking of those young, university age, women, sitting there against the prison walls, replaying the histories they had heard from their parents. She said that, in writing the poem, she placed herself there with them, in the darkened cells listening to the first rain of the season. I followed her there too, to that dark and dank cell, attempting to submerge myself in the feeling of her words. It was not difficult to imagine as, if I had not left Nicaragua, I could have very easily been one of those incarcerated university age women. In her last line of her email, Gioconda told me:

“El poema se explica a sí mismo.”

“The poem explains itself.”

Despite this statement of simplicity, the true difficulty in translating Gioconda's poem was not only in the language but rather the preservation of the feeling behind it. Though the

nuance of the poem in Spanish brought me to tears in one reading, I felt that translating it into English was flattening it, draining out the emotion that the words carried. The frustrations of something missing, something soulful lost in the translated words, pursued me throughout my days. The experience reminded me of the Spanish saying:

"Donde hay confianza, da asco."

Which roughly means: "where there is confidence, there is disgust." For better understanding, one might liken it to the English saying, "Familiarity breeds contempt." My comfort within both the Spanish and English languages lulled me to a false sense familiarity form which I took the nuances for granted. This comfort created a disability in removing one from the other during the process of such a significant translation. The difficulty of looking at a word objectively as a translator, by stripping away my familiarity and regarding it with a new and all-consuming perspective, was a process that opened my eyes to an even deeper understanding of translation.

Works Cited

Belli, Gioconda. "La Verdad Encarcelada." September 22, 2019.

Gansel, Mireille. Translation as Transhumance. Forward by Lauren Elkin. Translated by Ros

Schwartz, Les Fugitives, 2017.

[/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view="link" color="#4a4949" icon="arrow" expand_text="Translator's Note(Espanol)" collapse_text="Esconder" ]

Entre Líneas de “The Truth Incarcerated”

De niña, cuando conocí a Gioconda Belli, me encantó su cabello rizado y su ojos brillantes. Le dije, con una certeza que ahora envidio, que quería ser una autora como ella. Aunque puedo recordar que me sonrió y me dio palabras de apoyo, ahora sé que seguir los pasos de Gioconda es más que un proceso de escritura. Gioconda Belli es una mujer Nicaragüense que no solo ocupa el papel de escritora reconocida, sino que también es una feroz activista de derechos humanos y manifestante. Hace cuarenta años, durante la primera revolución, sirvió como espía detrás de la escena para los revolucionarios. Ahora, en el levantamiento de la revolución, ella está en primera línea con su pluma como espada. Apenas se había secado la tinta en los nuevos libros de texto de historia cuando Nicaragua comenzó una repetición de eventos violentos de hace unos cuarenta años. Es una batalla contra la dictadura que, posiblemente, nunca terminó en primer lugar. Una rebelión en la que los soldados son estudiantes universitarios enmascarados que luchan por un futuro mejor contra un gobierno que solo se preocupa por su silencio. Impulsado por la determinación de destacar los traumas que están expuestos en la población nicaragüense, le envié un correo electrónico a Gioconda Belli por primera vez en años en busca de un poderoso mensaje para traducir a un público más amplio. Ella respondió el mismo día, enviándome su obra poética más reciente, titulada: "La Verdad Encarcelada.” En el pasado, mi experiencia con la traducción había girado principalmente a la traducción entre inglés y español de mis propios trabajos creativos. Como solo el escritor comprende completamente la intención detrás de su escrito, convertir mi propio texto a otro idioma fue un proceso natural que vino con poca lucha. También, ocasionalmente, he traducido largos pasajes entre inglés y español para el sitio web de mi familia. Esta forma requería poco más que una traducción literal directa y, como también vino con tanta facilidad, admití que no había pensado en los matices y significados detrás de las palabras. Completé estas traducciones de un solo, principalmente sin hacer referencia a un diccionario o tesauro. En estos cazos rara vez se nota la complejidad de entre los dos idiomas. Sin embargo, desde el momento en que me propuse traducir "La Verdad Encarcelada,” surgió otro proceso por completo. Ya no podía dejar de notar las discrepancias entre el español y el inglés, ya que estas son refinadas por el lenguaje poético. La poesía, descrita como "lenguaje del alma" por Gansel, fue menos una conversión literal entre dos idiomas y más una traducción de una sola alma a un nuevo cuerpo (6). Me sentí inspirada por la traductora Mireille Gansel y sus experiencias en sus memorias Translation as Transhumance con la traducción de idiomas contaminados por traumas históricos y presentes. Intentando confrontar mis inseguridades acerca de traducir un trabajo tan largo, de 44 líneas, decidí simplemente traducir el poema literalmente antes de profundizar en sus matices. Fue solo después de eso que escribí cada línea del poema, tanto original como traducida, en páginas individuales de mi pequeño cuaderno. Influenciada por el proceso de traducción de Gansel, garabateé un telaraña de pensamiento sobre las páginas mientras hice recuentos del significado de cada palabra, así como su contribución a todo el poema. Desde el inicio de la traducción de "La Verdad Encarcelada" o “The Truth Incarcerated,” me encontré con dificultades sintácticas y semánticas. El comienzo de estas dificultades se me presentó rápidamente en la primera línea del poema con la palabra “imagino.” En inglés, esta única palabra se traduce literalmente a “I imagine.” Antes, nunca había reflexionado sobre la ubicación de uno mismo en palabras singulares en español, pero ahora se planteó como una complicación. Agregar "I" a la traducción sería una proclamación de un punto de vista directo que estaba ausente en el original, pero evitar la adición significaba cambiar el tiempo o el contexto de la palabra en sí misma. Usar algo como "imagine" parecería un aviso para el lector. Mientras tanto, "imagining" dejaría al lector distraído y preguntándose quién podría estar imaginando. Aunque seguía insatisfecha, me encontré con el incómodo pero ambicioso: “(I) imagine.” Esta complicación de las palabras que definen el sujeto continuó durante todo el poema, apareciendo frecuentemente a través de “las," “les," y “los," que a menudo no tenía más remedio que traducir a las palabras impreciso de "they" o “them.” Gioconda también hace uso de la licencia poética, lo que dificulta aún más la búsqueda de una traducción adecuada al inglés. "Apretujamiento" en la línea 10 ni siquiera es una palabra "real" en español. Combina "apretar" con el sufijo “miento.” No estaba satisfecha al traducir esta palabra transformada en "confinement" o “constriction,” ya que nunca capturó por completo el sentimiento de acción inmediata contenido en una palabra como “apretujamiento." Al final, me encontré mirando mi palabra propia: “costrictment.” Para mí, esta era la única palabra que capturo el sentimiento de la original. Sin embargo, lo que quizás me dio la mayor dificultad fue la sucesión de verbos poderosos y llenos de acción en las líneas 20 a 23. "arrancarían" "enfundarían" "arrebatarían" Posiblemente originario de mi infancia en la granja, la palabra “arrancar" mantenía la connotación de desgarrar las plantas enraizadas después de la cosecha. Por esta razón, me decidí por "ripped" para transmitir la violencia de la palabra española. "Enfundarían" en la línea 22, tiene una miríada de significados dependiendo del contexto, como cubrir, encerrar o envainar. Sin embargo, en un intento por mantener el sentimiento que interpreté del poema, me decidí por la palabra “enveloped." Sin embargo, para "les arrebatarían el sol,” me sentí obligada a reorganizar la oración para retener el significado original. Aquí, el tema cambia de “las," refiriéndose a las jóvenes encarceladas, a “les,” refiriéndose a los otros sin nombre. Sin forma de definir esta diferencia en inglés, la línea se convirtió en: "The sun would be taken from them." Aunque yo inicialmente tenía la intención de traducir "arrebatarían" como “seize," la palabra española también se puede usar para expresar el acto de quitarle la vida a alguien. De esta manera, Gioconda indica sutilmente la muerte del sol, algo que intenté retener traduciendo la palabra como “taken.” El poema también me detuvo al decidir qué aspectos tradicionalmente españoles dejaría y cuáles eliminaría. Al traducir, fue una decisión deliberada abandonar el signo de interrogación al principio de la oración. Ahora, en la era de la comunicación tecnológica y el creciente dominio del inglés, el signo de interrogación invertido está desapareciendo rápidamente de la existencia. Debido a esto, sentí que sería casi sacrílego eliminarlo y lo dejé como un recordatorio del idioma español. Encontré otra instancia de la historia española en la palabra "acequias" en la línea 39. Acequias puede significar sequía en el español nicaragüense, pero también es el nombre de los cursos de agua coloniales españoles utilizados para el riego desde la época romana. Traducir esta palabra ambigua al inglés significaría hacer una elección para el lector entre estas dos definiciones, una decisión que no quise hacer. Decidí a dejarla en su forma original. Al traducir "La Verdad Encarcelada,” tuve que tener en cuenta constantemente los contextos históricos del idioma, así como el significado cambiante de las palabras frente a la revolución nicaragüense. Me recordó la forma en que la palabra alemana "sensibel" había cambiado para Mireille Gansel de "frágil" a "sensible" después de entender los traumas que había sufrido la lengua (34). Para reflejar el lenguaje y el sentimiento de la rebelión nicaragüense, realicé cambios sutiles, como traducir "sin" en la línea 12 como “free from” en lugar de “without." Sin embargo, descubrí que el idioma español en sí tiene poética que palabras en el idioma inglés no pueden reflejarse. Se perdió un ritmo sutil como la lluvia. Al encontrarme con esta insatisfacción, le pregunté a Gioconda qué sentía originalmente al escribir el poema. Me contó cómo había estado pensando en aquellas mujeres jóvenes, en edad universitaria, sentadas allí contra los muros de la prisión, repitiendo las historias que habían escuchado de sus padres. Ella dijo que, al escribir el poema, se colocó allí con ellos, en las oscuras celdas escuchando la primera lluvia de la temporada. La seguí allí también, a esa celda oscura y húmeda, tratando de sumergirme en el sentimiento de sus palabras. No era difícil de imaginar ya que, si no hubiera salido de Nicaragua, podría haber sido fácilmente una de esas mujeres de edad universitaria encarceladas. En su última línea de su correo electrónico, Gioconda me dijo: "El poema se explica a sí mismo.” A pesar de esta afirmación de simplicidad, la verdadera dificultad para traducir el poema de Gioconda no solo estaba en el idioma, sino más bien en la preservación del sentimiento detrás de él. Aunque el poema en español me hizo llorar en una lectura, sentí que traducirlo al inglés lo estaba aplanando, drenando la emoción que transmitían las palabras. Las frustraciones de algo que faltaba, algo con alma perdida en las palabras traducidas, me persiguieron durante mis días. La experiencia me recordó del dicho español: "Donde hay confianza, da asco.” Lo que más o menos significa: "where there is confidence, there is disgust." Para una mejor comprensión, uno podría compararlo con el dicho en inglés: "Familiarity breeds contempt." Mi comodidad tanto en español como en inglés me llevó a una forma falsa de familiaridad de sentido. Este consuelo creó una discapacidad al separar un idioma del otro durante el proceso de una traducción tan significativa. La dificultad de ver una palabra objetivamente como traductor, al quitarme mi familiaridad y considerarla con una perspectiva nueva, fue un proceso que me abrió los ojos a una comprensión aún mas profunda de la traducción. Works Cited Belli, Gioconda. "La Verdad Encarcelada." September 22, 2019. Gansel, Mireille. Translation as Transhumance. Forward by Lauren Elkin. Translated by Ros Schwartz, Les Fugitives, 2017.

[/bg_collapse]