by Olivia Xing

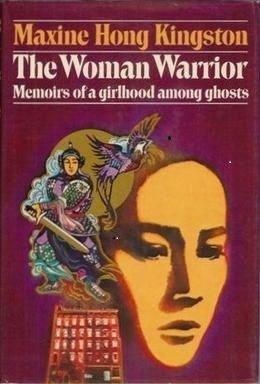

Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood among Ghosts is a different book. Although it is written by Maxine Hong Kingston in English and read mostly in the English-speaking countries, it involves elements of translation, in cultural terms. The talk stories, the legend of “Fa Mu Lan”, “barefoot doctors” and “the Big Six” … These idioms and traditions which have only existed as oral accounts in the Chinese context are translated into literary treasures and introduced to a broader audience. This distinctive characteristic of cultural translation brings along itself phenomenal popularity but also simultaneously brings about negative reviews questioning its cultural authenticity and its representative legitimacy. The critics, mostly Chinese scholars, accused it of using the “typical” oriental symbols to win western readers’ favor. By doing so, it stereotypes the culture and distorts the foreignness.

However, despite the ongoing debate on writer’s “ethic” to take readers’ opinion into consideration while writing, the spearhead of those criticisms is pointed in the wrong direction. Growing up culturally bilingual as an immigrants’ daughter, the second generation in the new land, Kingston should by no means categorized into the single cultural profile, which is also a stereotypical label created by a binary system. She is neither a western orientalist nor a representative for Chinese culture. As claimed clearly in the title, the book is a memoir. The dreamlike atmosphere, the illusionary talk stories, the fragmented structure and the assorted symbols taken together imitate a unique version of reality through the lens of memory. Kingston has no intention to lump together instances of cultural semiotics to attract eyeballs, but rather portrays a noteworthy experience of Chinese-Americans, a minor group not often called by name in literatures. To some extent, the popularity that The Woman Warrior has received can be considered as a victory of minor literatures, one characteristic of which is that “everything in them is political.” Because, according to Deleuze and Guattari’s interpretation on the minor Literature, “its cramped space forces each individual intrigue to connect immediately to politics,” the critics then consequently neglect the intimate and intensive self-analyzing part of the book. Their condemnation is scapegoating and is “scolding the locust while pointing at the mulberry” (a Chinese way of saying “abuse a person by ostensibly pointing to someone else”), to air their grievances towards the widespread conception of Orientalism.

The interculturality in Chinatown creates a motley world; the intertextuality leads to a more comprehensive unfolding of the text. The book is also translated “back” in Chinese, and as Benjamin claims, “a specific significance inherent in the original texts expresses itself in their translatability.” Translated to Chinese, the exotic becomes cliché and the shocking becomes exaggerating. Those elements after all lack a certain measure of translatability and can only survive in the English context. However, at the same time when they are washed off, the “inherent specific significance,” which in this case is the identity-seeking amidst childhood, poverty, family ad insanities, shines out of the text. “What is Chinese tradition and what is the movies?” Those intensely personal moments prove to be universal and always compelling regardless of the language, which also counters the aforementioned criticism.

Isn’t this process of deciphering the internal conflicts and searching for the vocabulary to communicate also translation? The book as a whole is a work of translation, wrestling with the utterance and the interpretation of meaning, with the verbal sign and the essence of the word. Then, isn’t every writer a translator? They confront this otherness, which emerges from the depth of personality in every human being and which has, since the collapse of The Tower of Babel, caused endless misunderstanding, in pursuit of a universal communication. Maxine Hone Kingston is another woman warrior who brought her own song from a savage land, a girlhood among ghosts. It translated well.

Works Cited:

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood among Ghosts. London: Picador Classic, 2015. Print.

Translated by Olivia Xing

Olivia Xing